I’ve been designing games for many years now, and one trend I’ve noticed in my own design style is that I continuously approach games from a more and more abstract perspective. I rarely start with a theme, like I did with Corporate America. And I often avoid complete systems with unique special rules and exceptions right from the start, which is how Shadow Throne began. Instead, I try to create something bare bones, usually experimenting with a single mechanic that interests me. I only build up from there if the mechanic seems promising on its own merits, without any bells and whistles.

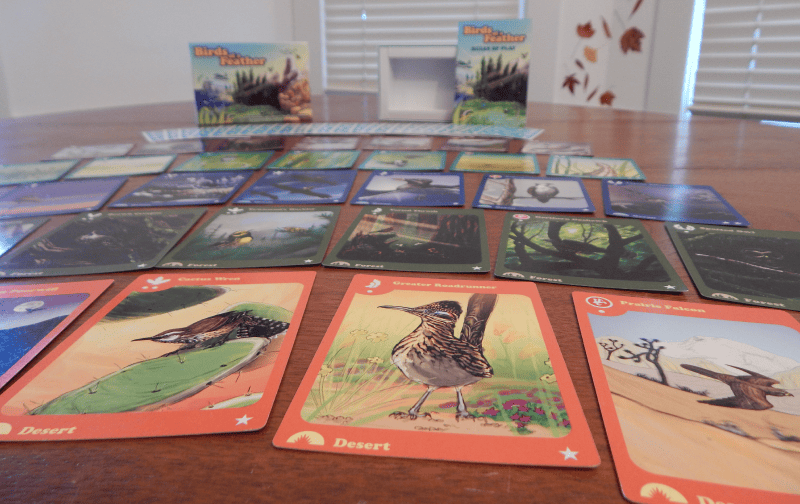

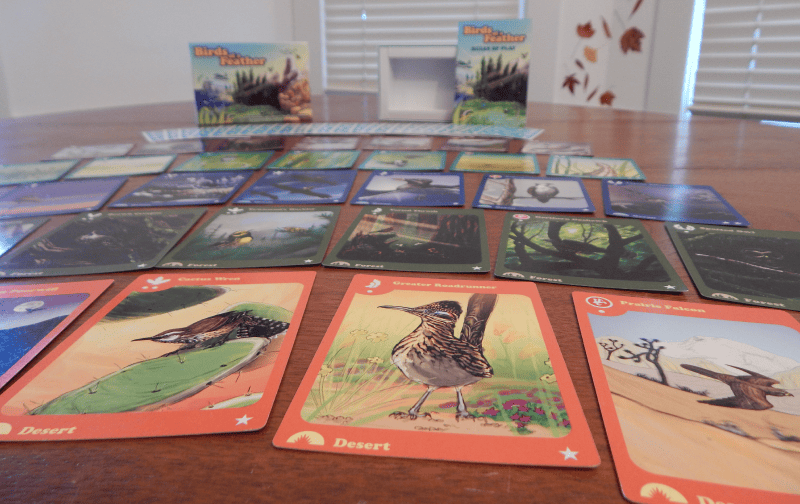

I have yet to release any games using this method (Birds of a Feather came close, but was more of a complete system right from the start). That said, even experimenting with new designs has led me to a realization: most games can be broken down into a few important parts, and understanding the different strategies that existing designs use for those parts is really helpful.

That’s because a new mechanic will often fit into one of those parts, so it’s useful to know what other parts you’ll need to fill out a potential game. Borrowing the other parts from existing games, especially early in the design process, is the fastest way to test a new mechanic. And even if you do end up coming up with your own support mechanics, experimenting with existing mechanics can teach you a lot about the new mechanic and guide you in designing the rest of the system to support it. But you may not even need to–many games can stand on their own with a single unique and clever mechanic.

Today I’m going to break down the parts that most games have. I’m sure I’m missing some, and the definitions can be a little murky and overlap a bit. Still, this is a good start, and my hope is that discussion in the comments might lead to identifying some more parts that are useful to be aware of and understand when designing. In future articles at the League of Gamemakers, I plan on delving deeper into some of these parts to discuss common mechanisms that designers use.

GOAL

Almost every game has a goal of some sort. Usually, goals are races, competitions over a limited time, or involve eliminating the opposition. Tying the goal to the end of the game, and therefore the duration of the game, is very important to consider when designing.

ACTIONS

If your players can’t take actions, you’ve got a simulation, not a game. Actions can take many forms, involving the core game system or other players. When thinking about actions, it’s also useful to consider the potential for simultaneous play, downtime, and turn order.

RESOURCES

Every game involves some resource management, even if it’s just in determining how to use one’s turns. But resource systems can be a great asset to games, helping to control pacing, differentiating strategies, and facilitating player interaction.

ACQUISITION

Many games, from Memory to Citadels to Eclipse, focus on collecting game pieces. It’s not uncommon for games to involve collecting many different types of pieces, and for those pieces to be layered. Amassing a collection fills a player with a sense of accomplishment, so I think this is a great aspect to include in almost every game.

SCORING

Scoring may seem straight forward, but there are actually many different ways of scoring, which can have dramatic effects on how a game plays. Especially in acquisition heavy games, a unique scoring system can be all that’s needed to turn a mediocre game into a really interesting gem.

ELIMINATION

Chess is a great example of a game that prominently features elimination. Over the course of a game, players lose more and more. And in some games, whole players become eliminated. In general, I think this leads to a pretty bad action arc, as players feel much weaker towards the end, but it has its advantages and is commonly used.

UNCERTAINTY

I intentionally use “uncertainty” instead of “randomness” because the latter is closely associated with dice and shuffled cards, which aren’t featured in every game. But uncertainty is a huge asset, creating suspense and excitement. Even perfect information games involve uncertainty, as the other players’ intended plans are always unknown.

INTERACTION

And finally we come to the biggest strength of tabletop games, interaction. When players can have nearly infinite solo experiences with a few taps on their phone screen, it is face-to-face social interaction with friends and family that makes board games worth seeking out and playing for many people. And the ways players interact in games is nearly as open as the number of games out there, including conflict, competition, cooperation, anticipation, bluffing, negotiation, obstruction, treachery, and many more.

With this list, I’m trying to capture major themes in game systems. I’m sure I’m missing some, so feel free to offer additional suggestions in the comments. And if you have a better name for these than “parts”, I’d love to hear suggestions for that too

I plan on covering these parts in a lot more detail in future posts. If you have any that you’re particularly interested in hearing about or discussing, please let me know in the comments. I’ll prioritize any requested topics!