Building prototypes is time consuming, tedious, and often expensive. So, you might be wondering: How good does your prototype have to be? How much money should you be spending? And how many copies should you make?

Out there in the design community there are different schools of thought. Some people say you should spend as little time and effort as possible on your prototypes. Other designers want their prototypes to be indistinguishable from published games.

Clearly, there is no one single answer for all people and all situations, but this piece will give you some things to consider and some examples to compare to.

PETER VAUGHAN

My perspective comes from my experience with self-publishing, and then as a game developer for Breaking Games.

From what I’ve seen, I think there are four possible stages for prototypes:

- The “it just needs to hit the table and get out of my head” version. And it’s probably broken. Production value? Like the cost to cut paper. You only show this to super close friends or play solo.

- The “game design night” version. You’ve banged on it, it needs to have clear symbols now, and chits that make it a bit more worth the time of your gaming group.

- The “can take it to a con” (or protospiel) version. This is similar to game design night, but you are in fact showing it to the public. Therefore, this step generally involves putting it in a box. Believe it or not though, you can still have all sorts of temp things – rulebook doesn’t need to be as polished, or temp pieces can be involved because you are still the host at any game session.

- The “send it to a reviewer” version. Now this is the money version. It should look like the game, as much as possible. Someone else will pull it out of the box, without you to caveat anything. It’s at this stage where I’d make sure the rulebook has been through it’s paces, laid out as you intend, the pieces are all representative of the final, there’s some level of art if not all of it. (This depends on KS vs non KS, but this is a reviewer we’re talking about! Pictures they take of it, no matter if they offer a disclaimer, will live on the internet).

NORV BROOKS

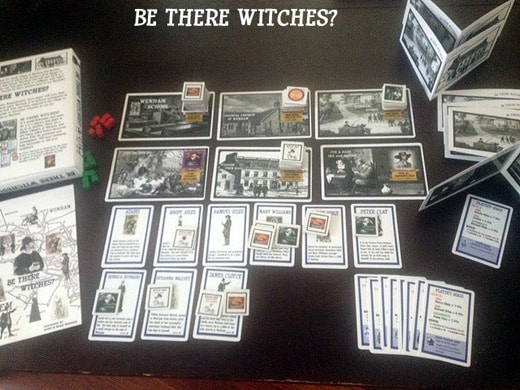

I’m a game designer on a limited budget; so, I develop my own prototypes. Creating a prototype is an element of game design that satisfies some of my creative needs. The main purposes for my prototypes are for playtesting and then for showing to publishers. When I get to the stage of seeking a publisher I try to have a polished prototype. I playtest my games at conventions which helps to make people aware of the game, and I use prototypes to present at publisher-designer speed dating events. Here’s an example of a prototype of the game Breaking News – Through the Generations in the presentation stage.

I turned to the Gamecrafter to make two prototypes for Be There Witches? partly because the game components were fewer and also because the components fit Gamecrafter’s templates. I must say I have more confidence in my Gamecrafter prototype when pitching to a publisher.

LUKE LAURIE

I make tons of preliminary prototypes that are each just a proof of concept. Once I’ve really hashed out a functional game, I try to make my prototypes functional, clear, and also aesthetically pleasing.

For The Manhattan Project: Energy Empire we did most of our playtesting and pitching with only two prototypes. This allowed one copy to be loaned out to other playtesting groups, and later to submit to a publisher, while always keeping the second copy to work with. These prototypes were updated approximately seven times prior to getting the game signed with a publisher.

After the game was picked up by Minion Games, during development, we did most of the work with about four prototypes. Each of these prototypes was pretty expensive (approximately $60 to $70), not because of any kind of fancy printing or boards, but because this game has a TON of components – something like 500 components.

For my first game, Stones of Fate, I used the Game Crafter to make prototypes, as did Cosmic Wombat Games once they signed the game. Stones of Fate had very few components, so it was relatively cost-efficient to make print on demand prototypes. I think they were originally about $16 for a full prototype, and much less than that for just the deck of cards. These glossy prototypes really helped this game get noticed.

JEFF CORNELIUS

That was the great thing about Stones, the prototypes were under $20! Can’t have enough of your game out there!

We made nine prototypes for Campaign Trail at $80 a piece. It was expensive and very time consuming work. We made two for Gen Con and the rest for reviewers.

SETH JAFFEE

As a publisher rep for Tasty Minstrel Games who receives and has to get people to play prototypes, I find a certain level of production value to be very helpful. If a game is physically hard or annoying to play, it won’t go over well.

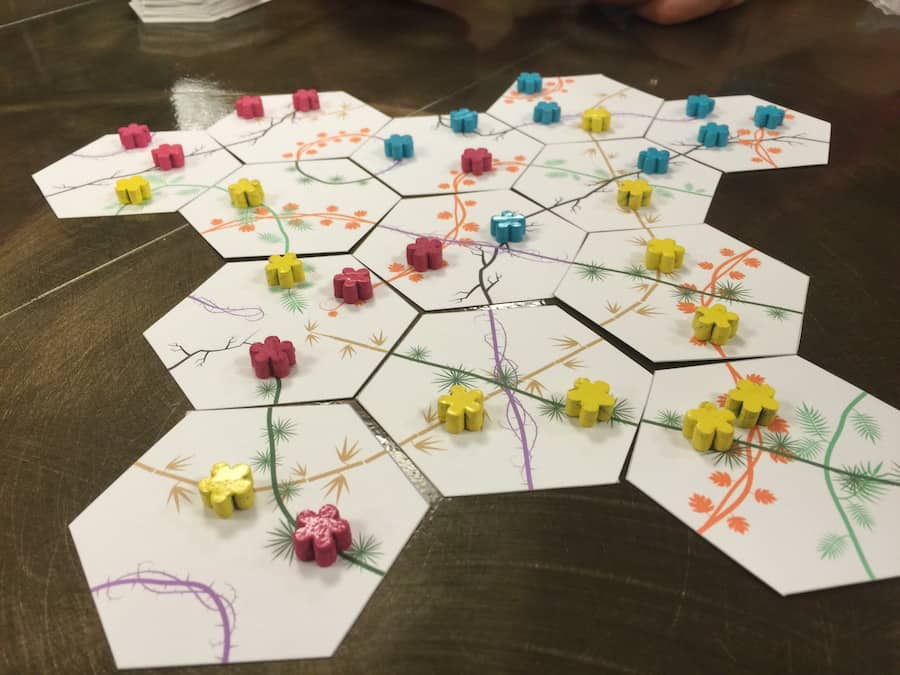

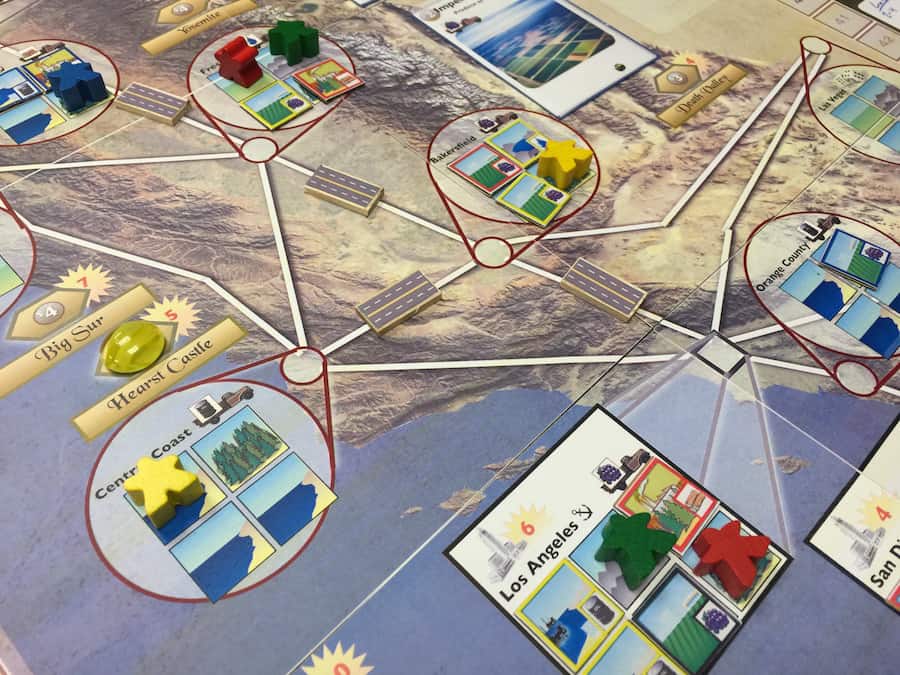

MORE SAMPLE PROTOTYPES

The following images were taken at various events and show playable prototypes. With these examples, you may have better perspective on if your own prototypes are good enough for your purposes.