Today I continue looking at the basic elements that make up tabletop games with Elimination. The previous articles can be found here: Goals, Scoring, Actions, Resources, Uncertainty, Space and Time, and Acquisition.

These days, “elimination” is almost a bad word to gamers. That’s largely because player elimination, once close to a default inclusion in any game, has fallen out of favor in a big way. But player elimination is only one form of elimination, and even it has its uses.

In a sense, all games feature elimination, since all games come to an end, making turns a dwindling resource. But the more common use of the term, where players lose resources over the course of the game (including the ability to participate at all), is not universal. Still, it’s featured in enough games, especially classic games, that I consider it a core game element.

PLAYER ELIMINATION

Let’s begin with the elephant in the room: player elimination. In a game with player elimination, certain players can leave the game before others (often at the hand of their opponents). It’s worth noting that player elimination only makes sense in game with three or more players. “Eliminating” a player in a two player game is really just ending the game. A player is only really eliminated if the game continues without them.

Player elimination used to be common in many classic games, from Monopoly to Risk to Poker. It makes sense: eliminating all opponents is a natural ending, especially for a war themed game. But player elimination has fallen out of favor for its many weaknesses:

Players want to play. The most obvious problem with player elimination is that some players continue to play while others are forced to check their phones, a mortal sin at many game tables. Most people start a game because they want to play. By knocking players out, a game with player elimination is forcing players to stop doing what they’re there to do.

Erratic game time. If you’ve designed a game or two, you know that managing a game’s play time is one of the designer’s most important jobs. But in games with player elimination, game length can vary greatly. Often this is because players have some control over when other players are eliminated, and frequently avoid it. Erratic game time is not just bad for fitting a game into a busy schedule; it makes things worse for those knocked out of the game early: they don’t even know how long they have to wait before their friends are ready to play something else.

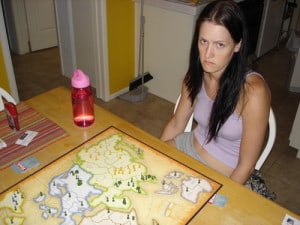

Games that prominently feature elimination like Risk can leave everyone feeling bad. Image from Board Game Geek.

Forced cruelty. It doesn’t just feel bad to get knocked out of a game. For many people*, knocking your friends out of a game feels just as bad. And in games where a player’s goal is to eliminate the opposition, players are often forced to attack each other, leaving everyone feeling bad.

*Definitely not everyone. You know who you are.

Despite these problems, player elimination has actually seen a resurgence in recent years. Very popular games like King of Tokyo, Coup, and Love Letter all feature player elimination at their core. How do these games get away with it?

First, these games tend to be short. When a game is quick, missing half of it is still missing less play time than when you’re are waiting for other players’ turns in longer games. And in games like Love Letter, players are eliminated from quick rounds rather than from the overall game, so they can look forward to playing again before long.

Another trick is making attacks untargetted or uncertain. In King of Tokyo, players don’t decide who they attack, they just decide whether to attack or not. In Love Letter and Coup, players often attack without having a very good chance of succeeding. This can make players feel less responsible for killing their friends.

Even though player elimination has its place in modern board gaming, I’d generally recommend staying away from it. Consider if there’s some alternative that will naturally fit in your game, and only fall back on player elimination if it’s crucial.

In Small World, losing your fighters can actually be an exciting thing. Image from Board Game Geek.

Small World does an excellent job of avoiding player elimination in a genre where it seems impossible. Similar to Risk, in Small World players fight for control over territory, killing the other player’s fighters in the process. But when a player becomes weak enough, instead of leaving the game, the player gets a fresh start with a new team of fighters, turning something that would normally feel bad into something exciting.

OTHER ELIMINATION

Players are just one of the things that can be eliminated over the course of a game. Many games feature resources and other aspects that become eliminated. For example, in Hearts, players start with a whole hand of cards, but use one card each turn and end with none left. And in Chess, players begin with a quarter of the board filled with their pieces, but lose them as the battle rages on.

So how does including elimination in a game affect it? Elimination can have a huge impact on a gameplay experience, and the impact is often both positive and negative. Here are a few thoughts on how elimination might impact your game.

Elimination creates a natural ending. Many traditional games feature player elimination as an end game state, but other types of elimination can work just as well. Running out the clock, burning through a deck of cards, or defeating all of the enemies all give a tangible, understandable end game condition. If you’re not sure how to end your game, consider introducing elimination as a countdown timer. Who knows, you might already have something that’s being eliminated over the course of the game you can repurpose as a countdown timer!

Elimination still feels bad. It may not feel as bad as being fully eliminated from a game, but losing resources or units still feels bad. This is especially true when other players are doing the elimination. When players have to work hard to acquire something, really question whether it should even be possible to lose that thing.

Elimination creates meaningful decisions. Losing something is a significant consequence. If players eliminate options with every choice, every choice will feel important and tense, which can be a great boon for a game.

Elimination fosters strategy. Games like Hearts achieve much of their strategy through elimination. Players know what their options are at the beginning of the game, and must plan how they will use those options to maximize what they’re dealt. Each option used is an option lost, so players must carefully evaluate the relative value of each option at different points throughout the game, creating interesting choices with long term consequences.

In drafting games like 7 Wonders, a player’s first choice often has the most options but the least direction, potentially overwhelming new players. Image from Board Game Geek.

Elimination can overwhelm new players. When players begin the game with all the resources they’ll ever have and lose them over the course of the game, as they do in Chess and 7 Wonders, early decisions can be the most difficult and the most significant. Generally, this is the opposite of what you want in a game: you want a game to start simple and become more complex as players become more familiar with their objectives and options.

Elimination can turn the end game into a slog. Just as elimination can create an overwhelming early game, it can make the end game anti-climactic. Fewer options generally mean simpler, less meaningful decisions, and fewer resources mean players feel weaker than they did at the beginning of the game. Again, this is generally not the experience players are looking for in a game.

Elimination can both help and hurt a game. These days, games are generally designed to make players feel more powerful over the course of the game, so elimination tends to take a back seat to acquisition. Still, it has an important place in many games, and is certainly worth your consideration during the design process. Used strategically, elimination can add a lot of meaning to a game without taking too much away from the play experience.