Today I’d like to continue examining the basic elements of tabletop games by discussing scoring. In my last article, I discussed goals in games, and given that scoring is closely tied to the goals of many games, it shouldn’t be a surprise that I’ll be referring to that article quite a bit today.

RACING VS COMPETITION

In my article on goals, I suggested that the goals of most games can be broken down as races or competitions. In races, players strive to reach a particular score first. In competition games, players strive to reach the highest score by the time the game ends.

I bring these up today because competition games tend to have more room for interesting scoring. In racing games, it’s often not even apparent to players that they are scoring. For example, instead of collecting “points”, they might be moving spaces on a board. You and I know that those spaces can be thought of as points to better understand how the game works, but the player probably won’t make this connection. Because the scoring is fairly hidden in racing games, it is usually simple and straight forward.* For that reason, I’ll be focusing on competition games in most of this article.

That said, don’t be seduced by the allure of a complex scoring system if your game doesn’t need it. As designers, we’re often drawn to complexity, especially when it gives us finer grained control over our creations. But complexity is a drawback for many players. If you can get away with a simple scoring system, or better yet one that is completely hidden, I highly recommend going for it.

HIDDEN SCORES

Should the players be aware of each others’ scores throughout the game? The answer to this question is different for different games.

If scores are hidden, players who are losing might feel more invested in the game throughout, since they won’t know they’re losing. It also opens up strategies that involve keeping a low profile. Additionally, keeping scores hidden means players can’t get distracted by computing scores midgame, which can otherwise slow a game down.

On the other hand, some games benefit from players knowing each other’s scores. This is especially true for games where players are expected to attack the leader, but many other catch-up mechanics require the player’s scores to be known as well. Plus, players can sometimes bash the perceived “leader” in hidden scoring games, only to discover that the targeted player was in last place.

It’s possible to take a hybrid approach for many games. Some part of the final score is public knowledge, while other parts are hidden until the end of the game. The latter part might be explicitly hidden, or it might just not get computed until the end of the game. Either way, this can give the players an idea of who’s doing well during the game while still maintaining suspense until the actual finale.

WHAT SCORES?

In Tokaido, almost every action directly results in scoring, revealing many different strategies.

In many games, there is a single way to score. In other games, there are multiple ways to score, sometimes many. At the most extreme end of the spectrum are “point salad” games, where almost everything the player can do results in points.

Games where a single thing results in points tend to be simpler and more streamlined, but not always. They certainly help focus the players.

Using many ways to score can help reveal different strategies to players and will encourage them to explore more. Being able to adjust the point value of different actions or resources in a game can also make it easier to balance.

SCORE GRANULARITY

In some games, a winning score is 3 points. In others, it’s 300. That’s a big difference, and it makes a big difference on how the game plays and feels.

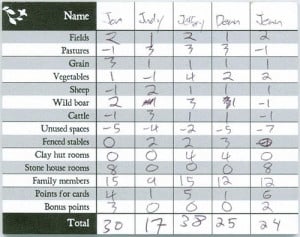

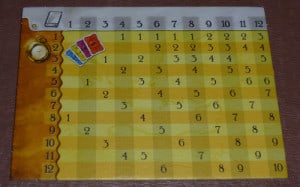

Once scores get above 10 or so, players often need assistance with the math, like these score sheets from Agricola.

In low scoring games, each point is precious. When scores get high, individual points don’t matter as much. You as the designer tend to have more control, too, and slight changes in scoring can help balance different parts of the game.

But it’s always important to remember that people will be playing your game, and many of them aren’t great and probably don’t enjoy math. Keeping scores low means your players can figure out their scores without using paper or special components, and will help avoid a potentially disappointing math-problem finale.

SCALING POINTS

Scoring can change value over time. For example, a scoring move can be worth 1 point in the early game, and 5 points in the later game. Scaling scores like this over the course of the game can help make a game feel more exciting as it approaches the end, and can also help mitigate early game advantages.

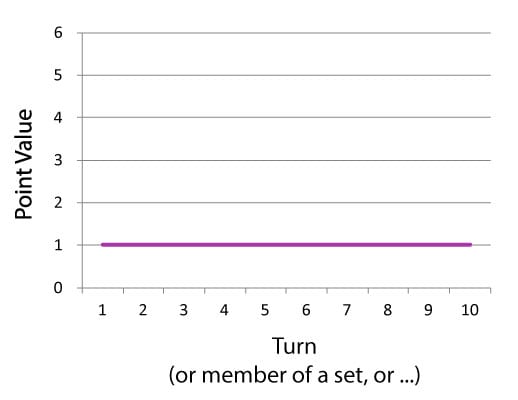

I like to visualize scores in my games as graphs. (This is useful for things other than scores, too!) When your game has no scaling, it looks like a flat line:

Scoring that doesn’t scale.

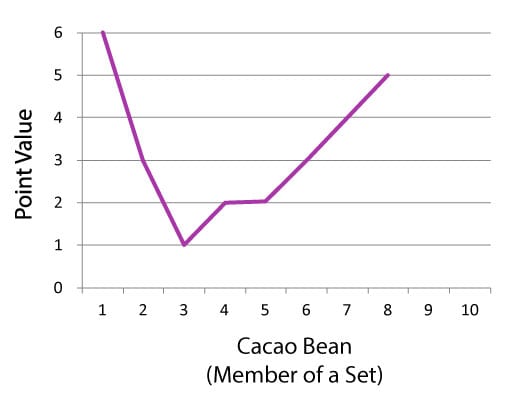

Note that the x-axis could be time (like turns), progressing through stages (like the different decks in 7 Wonders), the number of members of a set (a bonus for collecting multiple blue cards, for example), or really anything.

When something gets more valuable based on what you’re measuring on the x-axis, it moves up as the graph goes right. (Usually you don’t want the graph to go down to the right, because that means the early game is more important than the late game, a good way to eliminate a game’s buildup.) But how much the graph goes up can have a big impact on the pacing of the game and the incentives of the players.

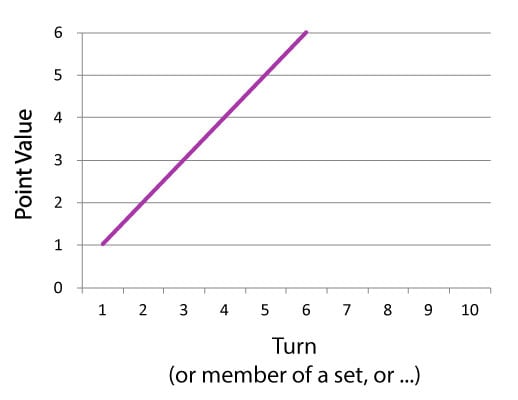

One common form is triangular scoring, where scoring scales up linearly (the first is worth 1, the second is worth 2, etc):

Triangular scoring.

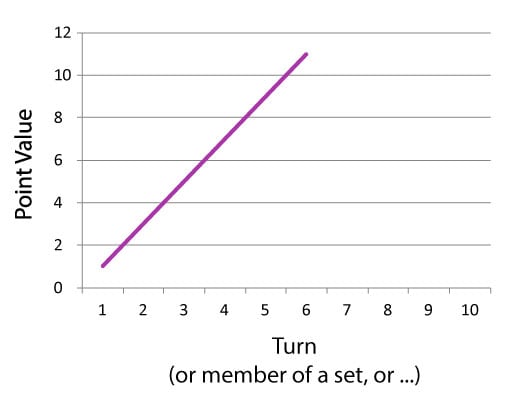

Square scoring is also common. Here, a new scoring event increases the value of all previous events (so one is worth 1, two is worth 4, three is worth 9, etc). I didn’t realize it before writing this article, but triangular and square scoring are both linear, with square scoring having a slightly steeper slope! (Note the scale is different along the y-asix in the below graph.)

Square scoring.

The exact scoring system you use should be totally dependent on the particulars of your game. The graphs can easily get out of control quickly, so making sure the game ends before scores start skyrocketing is important. But otherwise, you should test different trajectories to see which give the experience and motivation you want your players to have.

The unusual curve for scoring beans in Cacao. Sometimes, a game needs a funky curve!

MULTIPLIERS (AND OTHER MATH)

It’s tempting to add a lot of math to a scoring system to make it unique and interesting. Multipliers are a great example. Multiplying your score is always very exciting and motivating. But going down this path is dangerous for two reasons.

First, it can make scores vary widely. How much scores should vary is up for debate, but I don’t like having the last place player with less than 60% of the first place player’s score, preferably closer to 70%. To some degree, this is out of your control–you can’t make players make good choices. But adding extremely swingy scoring, like multipliers, can quickly turn a close, exciting game into a one-sided beating with no suspense.

Components, like this grid from Thebes: The Tomb Raiders, let you incorporate complex math into a game without burdening the players, but come with their own costs.

Second, math. There’s really no limit to what kind of crazy math you could incorporate into your game to make the scoring nuanced and interesting, but that doesn’t mean you should. I will say again that math isn’t fun for most people, and math that seems simple to you (like multiplication), can be challenging and potentially embarrassing for your players. (This of course depends on your target audience… hard core Euro and war gamers might have more tolerance for math than others. Just realize math will impact the potential audience of your game.) For my games, I try to keep math limited to addition and even shy away from subtraction or negative numbers. It’s not a hard and fast rule, and your limit might be different than mine, but it’s worth thinking about what your limit is.

All that said, with clever component design it’s possible to hide some of the complex math from your players while still retaining it in your game. Consider if there’s a way to make the game do the math for your players.

RELATIVE NUMBERS

If you haven’t already read my article on relative numbers, check it out. Having mini-competitions in games for fixed points (think longest road in Settlers of Catan) can create some interesting scoring opportunities that are conceptually simple but are still dynamic and interactive.

LOSS AVERSION

If you’re not already familiar with loss aversion, I highly recommend reading about it and other psychological phenomena in a book like Thinking, Fast and Slow. The basic idea is that people are more resistant to losing something than they are excited about gaining that same thing. What this means for your scoring system is that adding negative numbers or penalties will have a bigger impact on player motivation than offering rewards, even if they have the same affect on gameplay. If there’s something you really don’t want your players to do, add a penalty.

SETTLING THE SCORE

Scoring is hugely important aspect to many games. And some games, like Coloretto, stand up largely because of their unique and engaging scoring system.

Given the many different ways to handle scoring, it’s worth taking some time to think about what your specific game needs to create the greatest player experience you can!

Do you have any other thoughts on scoring? Are there any scoring variants I missed? Let me know in the comments below!

* Though not always. Take Lewis & Clark, for example. This is a racing game where players try to reach the end of a track first, but different parts of the track involve different terrain, so you have to score the right kind of “points” at the right time.