Matt Leacock is one of the rare individuals who has been able to fulfill his life-long dream of becoming a professional board game designer. Buoyed by the success of his mega-hit game, Pandemic, which has sold over a million copies, Matt was able to transition from being the Chief Designer at Sococo to being a full-time board game designer in 2014. To date, Matt has designed a dozen stand-alone games and half dozen expansions, as well as been nominated for the Spiel de Jahres three times. Matt’s recent co-design effort with Rob Daviau, Pandemic Legacy Season 1, has shot to the top of the BoardGameGeek rankings as the #1 rated game. Besides the Pandemic franchise, Matt’s other great success has been the super-accessible Forbidden Island, a game he likes to give to people who don’t usually play games, to introduce them to the hobby. I had a chance to talk to Matt via phone recently to ask him about cooperative games and legacy games.

What is the story of your first publishing success?

I brought my Pandemic prototype to Alan Moon’s “Gathering of Friends” for three successive years and kept revising it. On the third year, I pitched the game to a half dozen publishers and got a number of them interested. Among those publishers was Zev Shlasinger of Z-Man Games. I grabbed him right as he was leaving for the airport and gave him a quick pitch. He got back to me soon after and agreed to do the game. I had no idea what that quick pitch would eventually lead to.

What advice would you give someone who wants to become a full-time board game designer?

I’d encourage aspiring designers to start off designing part time as it’s impossible to maintain any kind of regular income before you have a successful product in the market. It’s probably best to find a career in an adjacent field, work on games in your spare time, and build up a portfolio of intellectual property. If you’re lucky, your games will be successful and you can make it work. I think it’s similar to becoming a writer, poet, or musician – it’s really tough to break in. I count myself lucky that my games have continued to sell after their initial release.

Why design cooperative games?

My wife and I played Reiner Knizia’s Lord of the Rings game in 2000 and the game really hooked me. I was surprised how much emotion a cooperative game could generate, and loved the fact that win or lose, Donna and I always had a good time together playing it. That made me wonder if I could design a game that captured the same magic.

I also really enjoy the puzzle-like nature of designing cooperative games. It’s like writing a computer program in cardboard.

What are the elements of a great cooperative game?

A GOOD COOPERATIVE GAME GENERATES A LOT OF EMOTION AND PULLS YOU IN.

Pandemic, for example, generates alternating waves of hope and fear. You feel really challenged and freak out. Then you begin to think you have things under control… until you get pummeled again. The challenge also needs to be at an appropriate level for the player’s skill level. As a game designer, you need to provide feedback loops (so the game adjusts according to the player’s performance) or options so the players can select the difficulty level that’s appropriate for them.

What cooperative games do you play from other designers?

I don’t play very many, because I work on them so often. Playing can feel like work because I spend so much of my time analyzing the design. I did, however, play Time Stories recently and enjoyed that a lot.

How do you feel about new cooperative games that seem to take a Pandemic as their starting point?

I’m just glad that Pandemic has held up so well. Every time one of these games is released, it invites comparison – and I think that’s ultimately good for sales.

If you were to mentor a newer designer designing their first cooperative game, what would you say?

YOU ARE DESIGNING AN INTERACTIVE SYSTEM. YOU NEVER REALLY KNOW IF THE SYSTEM WILL WORK UNTIL HUMANS INTERACT WITH IT.

Watch your players very carefully as they play your game and don’t rely too much on self-reported data. Watch for engagement: are they looking at their phones or are they leaning into the table and talking continuously about their options? Watch for confusion: when do they stop and have a rules question? Listen to the language they use when describing the objects and actions in the game. Are they the words that you chose or something else? Watch for errors: are they making mistakes? If so, would the game work more naturally if the rules were changed to support they way they think is the correct way to play?

What is your target win frequency for easy mode?

It depends on the game. I try to design the game so there is a good chance you will lose on your first try (assuming you’ve selected the appropriate difficulty level for yourself) and not blame the game for your loss. That keeps players coming back to see if they can improve their performance. Rob and I have a slightly different approach for the legacy games we work on together. In those games we try to design a 2:1 (win : loss) ratio since players can’t repeatedly play the same month. In those games we need to make sure we don’t trash the players’ morale while also ensuring the game is challenging enough that they don’t get bored.

Is the so-called alpha player problem something you worry about in your design process? If so, any tips for alleviating the alpha player problem?

I don’t worry about it so much. It’s most commonly an issue with players of mismatched skill levels or with players that don’t know each other very well. For example, I think it’s a bigger issue with players at conventions playing pickup games rather than with groups of friends playing around the table.

As a game designer, I’m always interested in techniques that can reduce the effects, but I don’t think it can be eliminated altogether. For example, in Pandemic: The Cure, players roll their own dice and feel a greater sense of ownership over them. I’ve never seen a player reach across the table and roll another player’s dice! There are other techniques you can use (hidden information, possibility of a traitor, and so on) but those also change the nature of the game and I’m reluctant to include them unless they’re a part of the core game.

The fact that players exhibit this behavior (among others) in fully cooperative games makes these games an interesting training ground. For example, the University of Leicester Medical School runs a training exercise for medical students (80 at a time!) on cooperation, communication, and collaboration using Pandemic. In the program, the players are observed by trained facilitators who code their behaviors as they play. After their first game, players receive feedback from the facilitators and play again. The groups that receive feedback win at a statistically significant higher rate than the control groups that aren’t told anything about their behavior.

In your games, different players have different powers and abilities. How do you playtest and balance so many combinations?

A lot of it is brute-force work, testing various combinations. I don’t try to do an exhaustive study; a representative sampling suffices. Over time, different patterns and approaches emerge for structuring and balancing the powers. Pandemic, for example, has a core set of roles that can be used as a benchmark. Often, it’s as simple as asking, “is this character stronger than the Medic?” I strongly favor a set of really powerful roles that are battling insurmountable odds, so I try to start with roles that sound impossibly strong on paper, then reign them in as necessary in testing.

How do you record feedback?

Early playtests are just me and a notepad. Once the game is stable enough to explain to someone else, I’ll bring in friends or other expert designers who don’t mind if I change the rules in the middle of the game. Once it leaves this messy cauldron and stabilizes, I’ll write up the rules and it’s ready to test with others.

I find that I get the best data if I mail prototypes to remote testers who record their sessions and upload video segments for me to watch. I then watch these and record observations, issues, and design ideas along with a timestamp so I can go back and review if needed.

The logs then morph into a prioritized list of changes for the next iteration of the prototype.

How do you decide which feedback is actionable?

The first step is to record it – if you don’t write it down, it’s too easy to sweep problems under the rug. If I see that a given problem is breaking the game (if the severity is high) it’ll get a bump in priority. Or if multiple groups are experiencing the same issue, I’ll know that I need to address it.

IT’S HARD TO EMPHASIZE HOW VALUABLE WATCHING PEOPLE STRUGGLE WITH A GAME IS – YOU DEVELOP A GREAT DEAL OF EMPATHY FOR THE PLAYERS AND IT’S A HUGE MOTIVATOR FOR IMPROVING THE OVERALL QUALITY.

Also, I don’t spend much time with questionnaires. People are terrible at self-report and questions like, “was it fun” are for the most part, a waste of time.

How did Pandemic Legacy Season 1 come about?

I think it was the result of a brainstorm with Sophie Gravel when I visited the Z-man office. We brainstormed different ways we could build on Pandemic’s success and came up with a bunch of ideas including a dice game (which became the Pandemic: The Cure). Amongst the crazy ideas was a “Pandemic Legacy” game. We laughed. I didn’t take the idea very seriously – I think I was put off by the amount of work I knew it would take and I didn’t have that many design cycles at that point. Or maybe I just didn’t know where to start. A few years later, I just started to jot some story ideas down for what a legacy version might look like and quickly filled several pages in my notebook. Then I thought, hey, this might actually be fun! I wrote to Z-man looking for Rob Daviau’s contact info to see if he wanted to join me on the project, and he wrote back with an incredibly short email containing the word YES in very large type. We’ve been working together ever since.

What were the design sessions like? Like pitching ideas for TV episodes? Did you figure out the whole story arc first and then fill in new mechanics, or did the story develop organically?

Yes, it was a bit like plotting out a TV show, although the notion of a “season” didn’t occur to us right away. We started with an idea for the beginning and ending and the major beats, then gradually built it out from start to finish, occasionally going back to fix earlier “episodes” for continuity and balance. There were twists and turns in the story that surprised and delighted us as we discovered them along the way.

What is the process for play testing a legacy game? Do you find people who commit to the entire game?

We used a mixed approach. We asked some people to play the game over multiple versions, while other groups only played one version of the season. Some groups played only one or a few months, while others tested the entire season. One group played 11 months of the game over 4 days at Gen Con while Rob and I observed.

Did you ever find mid-game or end game states that were ridiculous?

Yes! I think Rob and I broke the minds of one of our group while we were playtesting Season 2. You could see the look of consternation and anguish on their faces. Such are the perils of experimentation. We really did learn a lot about what doesn’t work.

Any advice to designers who are considering designing their first Legacy game?

It’s a lot of work so budget your time accordingly. Like any major work, you have to chip away at it gradually. Also, study up on what makes for good stories.

PEOPLE HAVE BEEN TELLING STORIES FOR THOUSANDS AND THOUSANDS OF YEARS AND THERE ARE WELL-KNOWN TECHNIQUES FOR STRUCTURING STORIES THAT ARE DIRECTLY APPLICABLE TO LEGACY GAMES.

You can also get inspiration from many other fields, whether it’s reading up on the techniques magicians use to direct attention, behavioral economics, world building, or simply doing a deep dive on the the topic your game is modeling.

Were you surprised at the success of Season 1?

Absolutely surprised at the magnitude of its success. We did notice that players and playtesters were binge-playing, often playing 3 and 4 times in a row in a single evening, so we did have high hopes.

How does it feel to have the #1 game on BGG?

Surreal.

What can you tell us about Season 2? Continuation of same story or new story line?

I can share a few facts. First, it’s a fully stand-alone game. You don’t need to play Pandemic Legacy: Season 1 in order to play it. Second, it’s scheduled to come out in 2017, although we haven’t yet announced a specific date. And third, Rob and I had a great time designing it.

We think you’ll be a bit surprised when they see it. I’m not able to share anything about the storyline at this point, though.

A question from a fellow Leaguer: Did Pandemic Iberia give you an excuse to visit Spain?

It was the other way around. I went to Córdoba and where Jesύs Torres Castro hosted me at the Festival of Games there. Later, when Z-man selected Spain to be the host city for Pandemic Survival, I reached out to him to see if he’d want to collaborate on a version of Pandemic set in his home country. Next year, I’ll be traveling to the Netherlands for the Pandemic Survival Championship. We’ll have to see if any games come from that…

A question from a fellow Leaguer: Was Chariot Race inspired by the Avalon Hill game, Circus Maximus?

It wasn’t. There is an interesting parallel, though. Roll through the Ages: The Bronze Age could be described as a 40 minute version of Avalon Hill’s Civilization. In a similar way, I think you could describe Chariot Race as a 40 minute game of Circus Maximus. But the core engine of Chariot Race is loosely based on a car racing game I did back in 2000.

Any other upcoming projects you want to talk about?

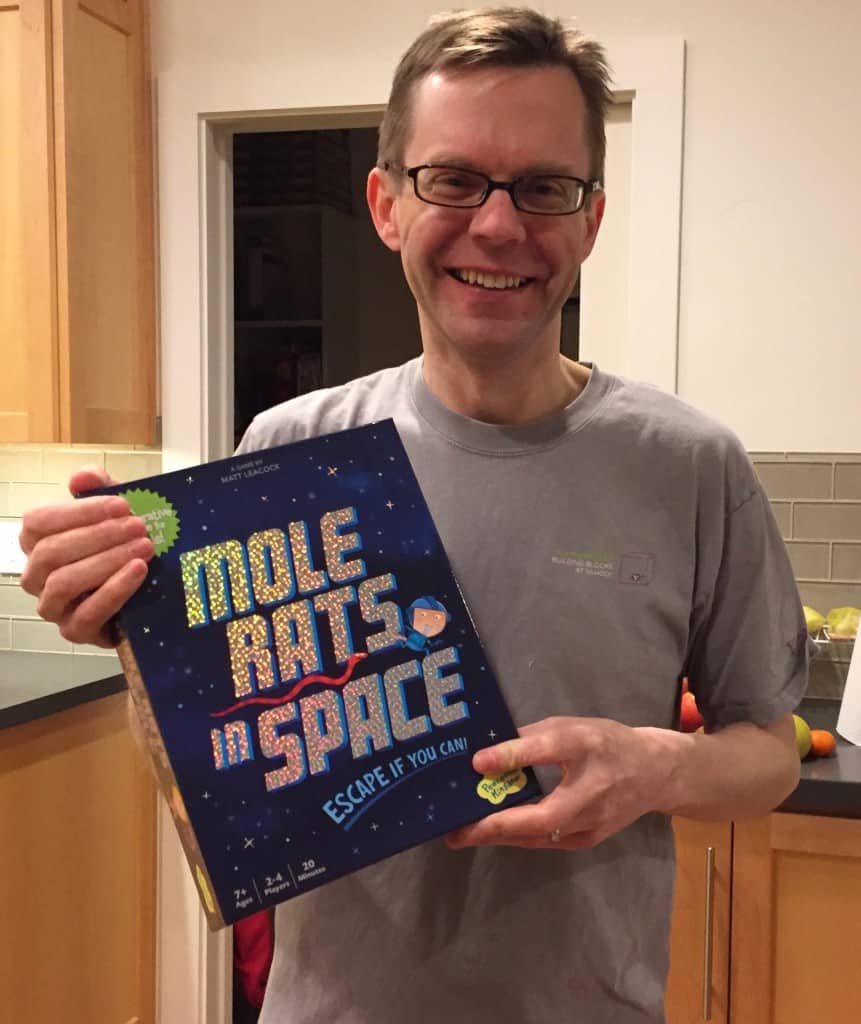

I have a new game for ages 7+ called Mole Rats in Space coming out in a few weeks. It’s the perfect introduction to cooperative games for kids. You and your fellow players all play mole rats on a space station that has been invaded by snakes. You all need race to the escape pod before you get bitten by a snake or blown out an air vent into the horrible black void. It’s kinda like a rated G version of Aliens. You know, for kids.

All photos are courtesy of Matt Leacock and used with permission.