ARE YOU READY TO START BUILDING?

In Part 1 we covered the first two steps of building a worker placement game: Research and Innovate. In this installment, we’ll cover the Build step. In Part 3 I cover the Refine step. In Part 4, I discuss The Manhattan Project: Energy Empire.

During your research, you studied the principles of worker placement, played worker placement games, and read about the experiences of other designers. Then, you formulated innovations by studying other games, drawing inspiration from your theme, playtesting other designers’ games, and/or maybe you “stole” an innovation or two from the list of free ideas.

Now, you’re ready to exchange your resource cubes for something bigger and better. It’s time to retrieve your workers and prepare for the next round. Take a meeple and place it on the Build space!

3. BUILD

Designers approach the process of building games in a wide variety of ways. Some go straight to their boxes of bits and start writing on cards. Some start by scrawling down notes and sketches in spiral notebooks. Others build games in virtual environments where they can run simulations. Still others prefer to use lists and formulae on spreadsheets to construct abstract mathematical representations of their games.

If you are a new designer, start with an approach that feels similar to the way you approach other creative work in your life. Go with what works for you and trust your own style, but continue to learn from others and adopt their techniques if they suit you.

This piece will not attempt to cover every facet of game creation. Instead, I will focus on three principles:

- BUILD ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS

- MINIMIZE ANALYSIS PARALYSIS

- KNOW THE VALUE OF A PLACEMENT

“Don’t make worker placement games multiplayer solitaire.” – Stephen DeBaun

BUILD ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS

This is an exciting time for the hobby of tabletop games. New and innovative games are being released almost every day. Kickstarter is allowing hundreds of independent designers and developers into the market. More people are joining the ranks of players and consumers of tabletop games. Websites and online forums allow collaboration and the sharing of ideas across the globe. All these factors, together, create a critical mass of innovation. This is, perhaps, the Gaming Renaissance. In this renaissance, there is no shortage of new ideas, and game concepts yet to be discovered have boundless and infinite potential.

Speaking of giants, Agricola(and its follow-up Caverna) is widely seen as the king of worker placement games. If you have a little time, check out this 100 part blog on the design, development, and publishing of Agricola by Uwe Rosenberg.

Designers are creative people, often swimming in vast pools of great ideas. But it’s important that we do not drown in a pool of innovation. When we approach our design work, we need to remember that many of our ideas, while brilliant, may actually be inferior to something that is tried and true. It’s possible that some common, ordinary, boring technique works better than the ingenious methods in our minds.

GAMES EVOLVE: EVOLUTION BY GAMER SELECTION

Think of some common game mechanics like drawing cards into a hand, victory point tracks, player colors, and so on, as being the products of evolution by gamer selection. There are so many elements of games that are similar, and should be similar, because they work well. Many lesser known techniques have been tried, and didn’t work well and became extinct. The familiarity of common mechanics creates a strong framework to hold up the key innovations of a game design, not unlike how the actual vertebrate backbone forms the framework for the vast diversity of vertebrates.

I’m not saying your game should be “Fjords of Foddercheap,” “Bone Age,” or “Daggercola.” You don’t want to make a cheap knockoff of another game, and nobody wants you to. Rather, look to your forebears to help your game have a stable foundation. Even if your game is really, really different, you can benefit by keeping some traditions alive.

While designing, build on the shoulders of giants by looking at how how other designers have found solutions for the design problems you are facing. Rather than inventing a solution from scratch every time an issue comes up, allow yourself to borrow solutions from other games. Then, slightly modify (mutate don’t mutilate) that solution to suit your game. In all likelihood, the solution you borrowing originated from yet another source.

MUTATE, DON’T MUTILATE.

For example, let’s say that you are building a worker placement game in which players must absolutely acquire a certain resource, say “Gold,” regardless of the strategy they choose. In your game, having gold is vital. When you test out your mechanics, you discover that having only one space, or two, or even three spaces for workers to acquire gold is not enough. Players can still potentially get locked out of acquiring the gold they need to make progress in your game. So you take a look at some of the games on your shelf and see how they solved similar problems.

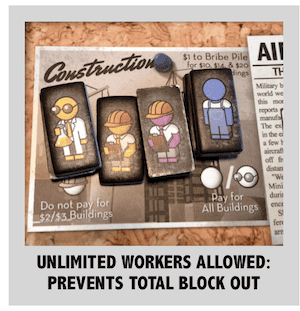

PREVENTING TOTAL BLOCK OUT:

- Manhattan Project: unlimited workers are allowed on “Construction” space.

- Stone Age: unlimited workers may go hunting for food.

- Euphoria: workers may displace(bump) workers off the board to take their spot

- Viticulture: Grande worker allows use of a location that is already full of workers.

Let’s say you decide to draw inspiration from the Manhattan Project and the “Construction” space. Unlike every other space on the Manhattan Project gameboard, the Construction space allows an unlimited number of workers to be placed there. Why? because constructing buildings is a vital part of the game for everyone, and locking players out of a vital part of the game is an “unfun” thing to do. So you create a similar space in your game, where unlimited workers can go get some gold, but then you innovate on top of that, and build a couple of “better,” exclusive spaces where players can acquire even more gold.

You have solved a design problem of your game, you have built on the shoulders of giants, and you are free to focus your creative energy on the truly innovative aspects of your game design.

“Make sure that the placement locations are well-balanced enough in their effects that the first few choices aren’t obvious. A mixture of long-term effects whose benefit is not immediately calculable and short term effects is always beneficial. Long-term or random effects will also reduce analysis paralysis.” – Tom Jolly

MINIMIZE ANALYSIS PARALYSIS

Analysis paralysis in boardgames usually describes a situation in which players cannot make timely decisions, often because the decisions are too complex, the choices are too numerous, or the consequences are too difficult to predict. Consequently, players lack the tools they need for effective decision making.

One of the appealing aspects of worker placement games is how well the structure lends itself to enabling players to understand and evaluate their options. The benefits of a placement are often easily visible on the board. The opportunity costs are likewise there to see. In building your own worker placement games, take steps to facilitate the decision making of players.

PREVIOUSLY ON THE LEAGUE OF GAMEMAKERS: “DESIGNING GAMES TO PREVENT ANALYSIS PARALYSIS” – PART 1 AND PART 2.

GAME DESIGN PRINCIPLES TO REDUCE ANALYSIS PARALYSIS

- Optimize the number and complexity of decisions. Good games limit the choices players can make, so they are not overwhelmed, but still let them feel like they’re in control.

- Optimize the amount of information. Players need sufficient information to take deliberate actions toward the goals of the game, but not so much information that there is always a perfect move to be found.

- Ensure variation in value. Some moves/resources/cards in the game should be better than others, and the advantages they confer should be visible. Varying value facilitates efficient decision making.

- Be consistent. Creating consistent mechanics that are uniformly applied throughout your game allows players to evaluate options more easily, and concentrate their mental energy on strategy, rather than procedure.

- Provide clear goals. If a game’s objective is too vague, players may not be able to see how useful their various options are. Provide visual cues, reference cards, or other means to let players know how well they are doing. This feedback will help them see the value of their choices, or lack thereof.

In Part 2 of my previous piece on analysis paralysis, I discuss in detail the following ten methods for reducing analysis paralysis. For more information, see the original piece.

METHODS TO REDUCE ANALYSIS PARALYSIS IN YOUR GAME DESIGNS

- BREAK DOWN TURNS INTO STEPS OR PHASES

- IMPOSE LIMITS

- REDUCE TURN LENGTH

- USE HIDDEN INFORMATION OR RANDOMNESS

- REDUCE OPPORTUNITY COST

- ESCALATE GRADUALLY

- PREVENT CATACLYSMIC CHANGE

- ELIMINATE OR REDUCE CALCULATION

- MINIMIZE VISUAL INFORMATION

- USE SIMULTANEOUS ACTIONS

KNOW THE VALUE OF A PLACEMENT

One approach to designing a game is to consider the fundamental unit of value in your game, and to determine the value of placing a worker. Is the fundamental unit in your game money or a resource? Is it movement on a track? Is it an action itself? A card draw? A victory point? What aspect of your game underlines all other aspects of the game?

Each time a worker is placed on the board, that action will turn the wheels of your game, so to speak. The placement will likely provide the acting player with a benefit, and may potentially create a cost or setback to other players. The acting player might gain a benefit like a resource, card draw, or other form of advancement toward a goal. Likewise, a player’s choice will potentially have an opportunity cost, meaning that by choosing one option a player may lose the chance to benefit from other options now or in the future. The opportunity cost may decrease the actual net value of a given choice. For more on opportunity costs, see Stephen DeBaun’s piece: “Adding Opportunity Costs: Army Building in Ars Victor.”

that action will turn the wheels of your game, so to speak. The placement will likely provide the acting player with a benefit, and may potentially create a cost or setback to other players. The acting player might gain a benefit like a resource, card draw, or other form of advancement toward a goal. Likewise, a player’s choice will potentially have an opportunity cost, meaning that by choosing one option a player may lose the chance to benefit from other options now or in the future. The opportunity cost may decrease the actual net value of a given choice. For more on opportunity costs, see Stephen DeBaun’s piece: “Adding Opportunity Costs: Army Building in Ars Victor.”

If you can establish a resource or action in your game as having a value of 1, then you can analyze balance in your game by comparing the relative value of the various choices based on that fundamental unit.

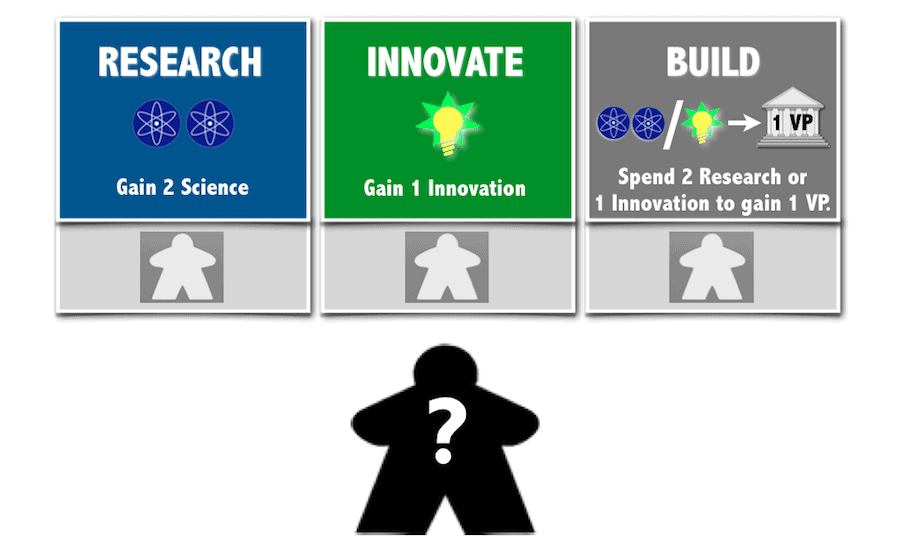

EXAMPLE:

Here we see three options available for our worker: Research, Innovate, and Build. For the sake of discussion, I’ll assign a value of 1 to the Science resource. With that fundamental unit established, I can determine relative values of the other spaces and also determine the typical value of the act of placing a worker, based on what the expected benefit would be.

Resource Values:

Science Resource = 1

Innovation Resource = 2

Placement Values:

Placing on Research = 2

Placing on Innovate = 2

Based on the Above, the value of placing a worker is 2.

WHAT IS A VICTORY POINT WORTH?

At a glance, it might appear that a victory point should have a value of 2, because 2 Science or 1 Innovation can be converted to 1 VP using the “Build” space. But in order to gain that victory point, a prior action is required to gain the resources. That action can be seen as a cost. Consequently, we can conclude that the value of a victory point is 4.

Now let’s consider how resources might be exchanged in this game, and what the benefit might be for the player.

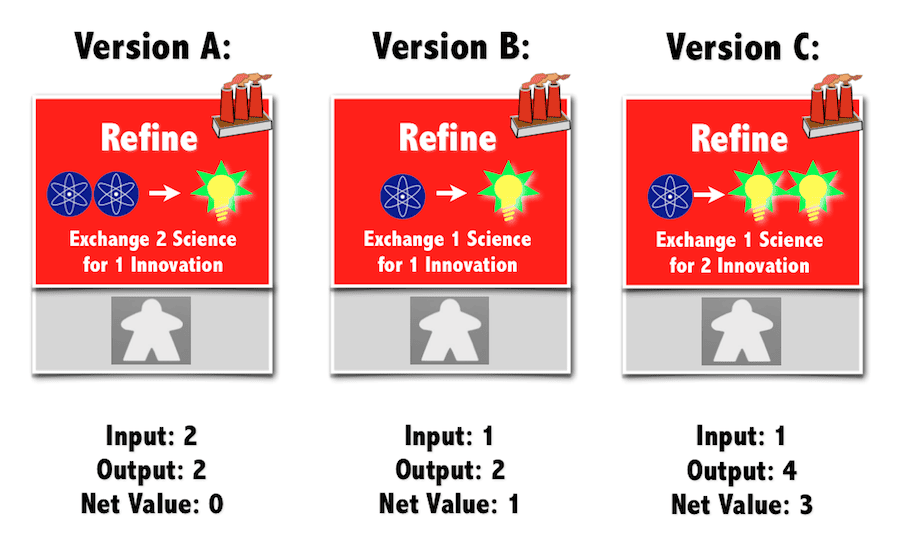

EXAMPLE: CONVERTING A RESOURCE

In these three versions of the “Refine” space, Science is exchanged for Innovation. At a glance, Version A might look like a fair conversion, but compared to the spaces above for “Research” and “Innovation” above there is no net gain of resources, and the player is also using up a worker placement action. We should expect a given space to offer a benefit close to the value of 2 previously determined. Version B is a slight improvement in benefit, exchanging a single resource for a single resource that is twice as valuable. But this exchange is still not as beneficial as using the Innovation space above. Version C offers the greatest value, and might even be seen as a “better” space than “Research” and “Innovate,” except that it still requires a player to have already acquired the science resource.

REALITY IS NOT SO SIMPLE

These examples are provided only to give a basic overview. As the game is played and spaces are occupied, the relative values of remaining options will shift. Some board spaces may have greater value earlier in the game, and others may be better towards the end. Different goals or different strategies may affect an individual player’s perception of value. Your game will likely be far more complex than what’s presented above, and the costs and benefits to the actions in your game will be dynamic and less easily quantifiable. Your game might not use any resources at all. Perhaps placing workers causes board movement or rearranging tiles. There’s nothing that requires a worker placement game be a “cube pusher.” Nonetheless, keep this concept in mind: Each time a worker is placed, it should generate a net benefit for the player, one that has the potential to help that player to move closer to achieving the goals of the game.

Avoid the situation where there is “no meaningful choice in placement as the game progresses” – Norv Brooks

WHAT WORKER PLACEMENT GAMES ARE WE BUILDING?

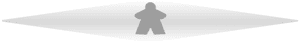

Several members of the League and our design colleagues have worker placement projects in the works. Some of these are described here. Christian Strain will be Kickstarting a worker placement game in May, 2014 called “Asking for Trobils,” which features a light space theme and bright orange artwork. Jeff Cornelius is designing a worker placement microgame that fits on a single business card and uses only 1 meeple, 14 cubes, and 2 dice. Stephen DeBaun has been experimenting with converting an existing design to worker-placement-like mechanic with his “Hundred King War.” Brad and Norv Brooks are building “Breaking News,” a game in which players build a news media empire. Mark and Christina Major have designed Chimera Station, a soon-to-be-published science fiction game where your workers can be upgraded with different body parts to help them accomplish their tasks in an intergalactic commerce hub. I am working on an energy/environmentally themed game called “Drill, Baby, Drill.”

This concludes the “Build” step of designing a worker placement game.

GO TO PART 3!

ALSO ON THE LEAGUE OF GAMEMAKERS

ALSO ON THE LEAGUE OF GAMEMAKERS

Here are a few other posts on the League of Gamemakers that may assist you in your game making:

- “GAME MAKING AS A SYSTEMS ENGINEERING PROBLEM“ – BY JEFF CORNELIUS

- “THE WORLD OF THE PLAY“ – BY KELSEY DOMENY

- “GAME MECHANICS THAT WILL PREVENT TURTLING AND GANGING UP“ – BY TOM JOLLY

- “WHAT’S IN YOUR PROTOTYPING COLLECTION?” – BY CHRISTINA MAJOR

ALSO ON THE LEAGUE OF GAMEMAKERS

ALSO ON THE LEAGUE OF GAMEMAKERS