When talking non-RPG tabletop games, mechanics make the game. Mechanics ARE the game. Themes and components can enhance games and create more immersive experiences, but the core of a game is ultimately the mechanics. If you are a designer, that’s where you should channel the vast majority of your creative energy. In situations where you must choose between preserving your theme and using the most solid, fun mechanics, go with the mechanics.

core of a game is ultimately the mechanics. If you are a designer, that’s where you should channel the vast majority of your creative energy. In situations where you must choose between preserving your theme and using the most solid, fun mechanics, go with the mechanics.

I don’t always take such a strong stand. I usually encourage designers follow their instincts. And they should – as long as they don’t neglect mechanics. Of course, opinions about this vary widely, as do the styles of different designers and players. For this piece, I‘m going to deliberately take one side. If you feel differently, make your case in the comments!

ALSO ON THE LEAGUE:

Part 2 of this series by Peter Vaughan: Theme is More Important than Mechanics

and Part of this series: Theme vs Mechanics: The False Dichotomy

GAME DESIGNERS SHOULD FOCUS ON MECHANICS

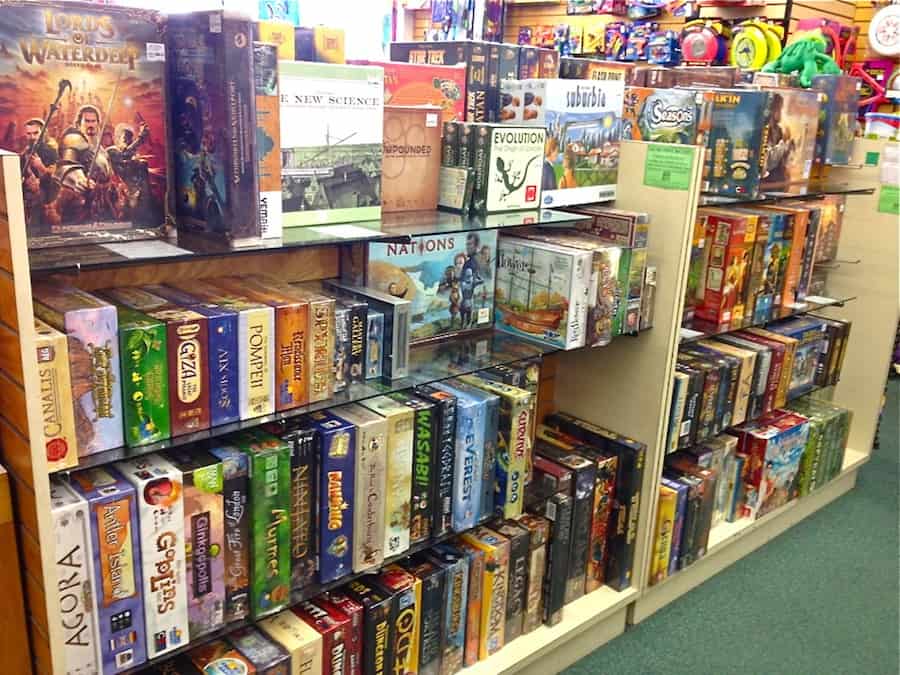

When you see a shelf of games like this one at Games of Berkeley, do you look for theme? Do you look to see what mechanics the game uses? Who the designer is? Publisher? Once you’ve purchased a game, what makes you want to play it more? To teach your friends?

DEFERRING TO THEME MAY HOLD YOUR GAME BACK

You may be so committed and dedicated to preserving your theme, that it may interfere with your design. You’re not building a simulation, and even if you are, simulations do not include every detail. People don’t actually get killed when flight simulations crash.

Take economic systems in games, for example. In the real world, if you’re going to make a little profit in business transactions, you need to sell things for more than you pay for them. You don’t get anything for free. When you do make money, the profit margin can be very small compared to the costs. But copying those principles exactly can make for a fiddly and un-fun game. In a fun game, you often will leave out some aspects of your theme entirely, and concentrate your mechanics on the things that are fun to do.

The game “Container” uses fabulous supply and demand mechanics that might make you feel like you’re a shipping mogul, but they’re far from the incremental value-added economics of the real world.

IT’S OK TO FOCUS ON MECHANICS

Over the last year or so, I’ve discovered that my best design work comes from taking a mechanics-centric approach. I have suffered some guilt over this because of some guidance from some of my colleagues in the industry. Advice on game design can often sound something like this: “Concentrate on your theme and let the mechanics flow naturally from it.”, “Focus on the story you’re trying to tell and everything else will naturally arise from that.” Those words sound nice, but they’re also kind of like new-age Facebook quotes. They make you feel good, but they don’t actually help you learn any practical skills.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m all about telling stories. I have three decades of experience designing and running dungeons and dragons adventures and a theatre background. But when I’m building a boardgame, no story is going to magically make functional mechanics for me. They might inspire a concept or two, but from there, I need to get down into the nuts and bolts, and draw instead from my experiences with carpentry, automotive mechanics, building and designing robots, doing science, and doing math. To build my game mechanics, I need something borrowed, and something new, fused together in a seamless, integrated system.

EACH ELEMENT OF A GAME SHOULD HAVE A MECHANICAL PURPOSE AND FUNCTION. IT SHOULDN’T BE INCLUDED SOLELY BECAUSE THE THEME DEMANDS IT.

I learned to feel ok about a mechanics-centered design approach through conversations with my friend and colleague Tom Jolly and by reading about the design process of Stefen Feld. Tom Jolly has had several of his designs re-themed. Stefan Feld builds his game systems to be fun and intriguing in an entirely mechanical sense, and then brings in theme late in his design work. In the words of Tom Jolly, “Theme is gravy.”

Like many designers, I enjoy inventing new mechanics, either from whole cloth or modified versions of existing mechanics. It’s perfectly acceptable to start piecing together mechanics and then go looking for a theme. It’s perfectly acceptable to build a mechanical system and let that system inspire a theme. It’s also perfectly acceptable to have no theme or a minimal theme. We have an entire genre dedicated to these games: abstract games.

PUBLISHERS MAY CHANGE THE THEME OF YOUR GAME ANYWAY

If you’re not planning on self-publishing, you’re eventually hoping to get your game into the hands of a capable publishing company. Imagine if a prospective publisher wanted to license your game, they really loved the feel of the gameplay, but they were not impressed with your theme. In fact, they hate your theme and everything it represents.

Do you walk away with your artistic integrity intact? Or do you accept the fact that the core of your game was never your theme at all, but the mechanics you built?

The truth is, re-theming games is incredibly common. Your theme isn’t your game. If a publisher really, really, loves your theme but not your mechanics they won’t publish your game. They’ll find another design using that theme with better mechanics.

There’s a list of games on Board Game Geek that were designed with one theme in mind, and subsequently changed by publishers, but this is far from a complete list:

Geeklist: Theme Changed By the Publisher

It will be your mechanics that distinguish your game, and your mechanics that will get your game published.

What’s your take?